Ichiro the Loser

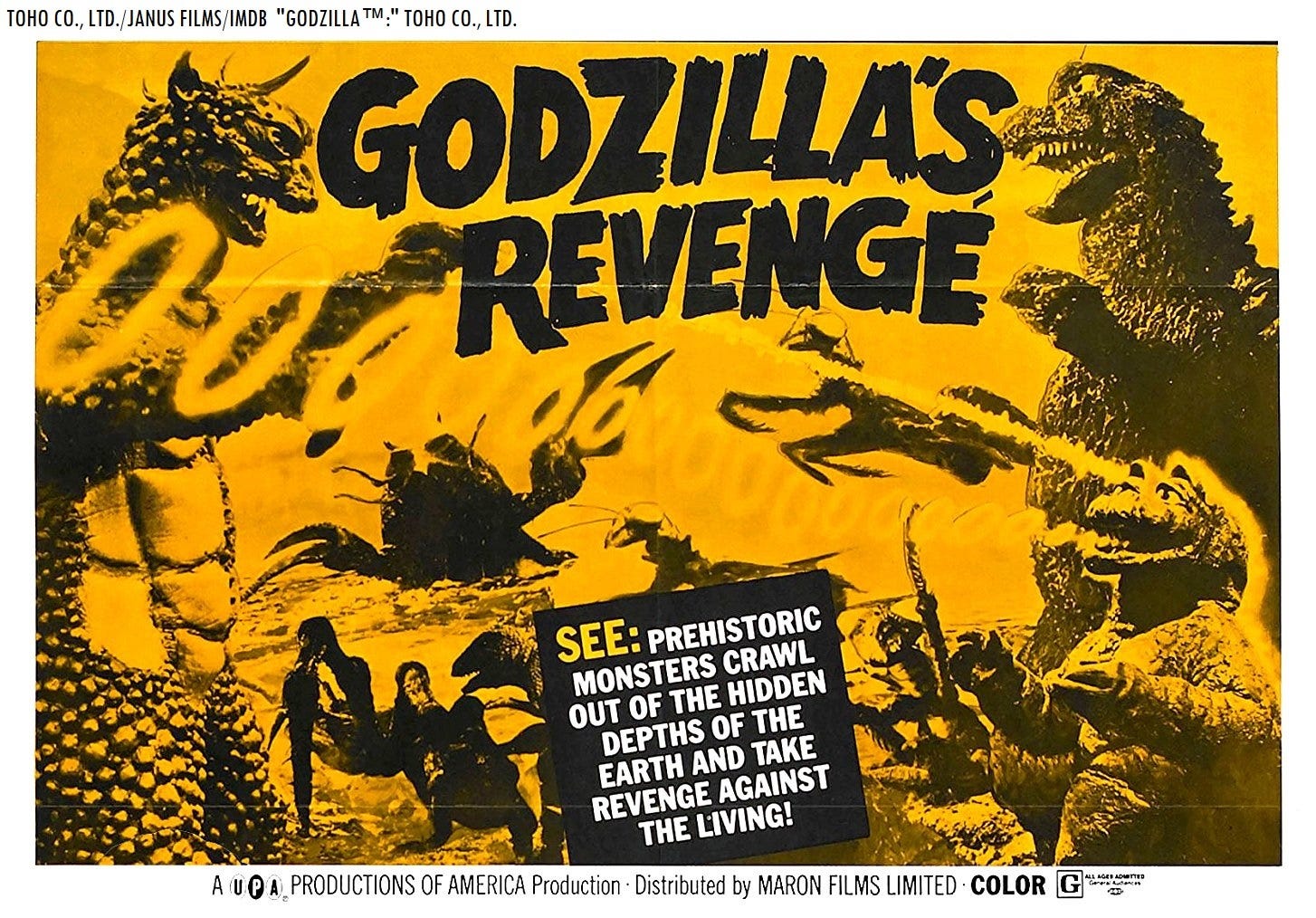

Godzilla's Revenge (1971)

Ichiro lives in dystopia. The kid walks home to an empty apartment every day after school, flanked by his only friend, a girl. A squad of bullies frequently if not constantly torments Ichiro on his walk, led by some douche named Gabara.

Even beyond the personal issues, Ichiro’s walk is far from scenic. It’s an industrialist nightmare. Massive smokestacks belch filth into the air, dwarfing, if not outnumbering, the human population. Factories, trains, cars, anything not specifically human is doing everything it can to poison the air, to spread those toxins around. Everything is dirty. The sky is a filthy, sooty color. The streets are a filthy, sooty color. Even the film is a filthy, sooty color.

Coming home one afternoon, Ichiro checks in on his toymaker neighbor, Shinpei, who shows him his latest invention, a radio giving kids stuck in this nightmare the illusion of escape – for example, to the moon. But Ichiro doesn’t want to go to the moon – he tells Shinpei he wants to go to Monster Island, an island somewhere off the Japanese coast where the government keeps Godzilla and Toho Studio’s other rubber suit monsters. See, by this point in the Godzilla series, 14 years in, some sort of Stockholm Syndrome had sunk into Japan: Godzilla has gone from nightmare embodiment of post-nuke terror to protector of humanity. Ichiro, not feeling especially connected to humanity as a whole, wishes Godzilla was his protector – he’d blow that bully Gabara’s ass away.

Like any latchkey kid, let alone one whose latch lies in a wasteland, Ichiro gets by off imagination. After another day’s alienation, he sits down in his parentless apartment and nods off into a dream.

In the dream, he’s on a flight to Monster Island. Lonely kid that he is, he hasn’t found a way to get what he wants without closing his eyes, so Dream Ichiro also nods off on the flight. When he awakens, the pilot announces the flight has set down on Monster Island. As you might assume, not a popular destination, even for tourists – Ichiro finds himself on an empty plane.

Unable to imagine how he might logically exit the plane, let alone where on the monster-covered island the airline might have set a landing strip, Ichiro sort of extra-dimensionally places himself on the island. The film’s colors invert and everything becomes swishy.

With the help of the movie’s editors, Ichiro now finds himself right where he wants to be: in the jungle, baby, watching, hidden, from a clearing as the towering Godzilla lumbers around.

Following the massive monster – from a safe distance – through the jungle, Ichiro makes a friend: Minilla, Godzilla’s dopey-looking kid from Son of Godzilla (1967), who, in Ichiro’s imagination, is his height, rather than Godzilla’s.

Turns out Minilla’s having bully problems too. His bully even has the same name as Ichiro’s: Gabara. Minilla’s Gabara, however, is not some love-deprived shit kid, but a psychedelic cat dragon with a tiny unicorn horn, tufts of red hair, and, appropriately, one of the most unsettling of the Toho sound designers’ many unsettling roars, something equivalent to a half-second of a cat getting its tail stuck, caught in a perpetual tape loop.

Godzilla wants Minilla to stand up to Gabara, but, Minilla tells Ichiro, he’s “chicken.” The version of Minilla Ichiro dreams up is particularly pitiful in the English dub, given a sad-sack Eeyore voice not even a mother could love, spending most of his time wandering rocks looking for god knows what. Case in point, Ichiro makes the mistake of asking how Minilla’s doing.

“Just feeling lonesome ‘cause I’ve got no friends.”

Of course, over the course of the film, watching Godzilla fight giant monsters and jet planes, both Ichiro and his imaginary friend Minilla learn to stand up to their Gabaras. The plot thickens as – back in the “real world” – the lonely walking routes of Ichiro’s life cross paths with bank robbers on the lam, who finally take the kid hostage when he wanders upon their hiding place. There’s some poetry to the overlap: both parties alienated from society, that bully Gabara undoubtedly on the path to follow that alienation to the bank robbers’ life of crime, while Ichiro, gifted with imagination, able to surmount the alienation – even if all he sees up there is the rubber gods of Monster Island. Applying the courage he’s developed through his mental trip to Monster Island, Ichiro is able to elude the criminals, leading them right into the cold embrace of the law. After that, taking on the school bully is a breeze. Ichiro’s girl friend even seems to be looking at him differently – not just as a bud, but, hey, maybe even a potential squeeze down the road. Ichiro has become a schoolyard pimp by way of Monster Island.

This isn’t all quite as fantastic and far-out as it sounds. Godzilla’s fights, which constitute a good half the movie, are all stock footage from prior movies, chiefly the last couple directed by Jun Fukuda, the aforementioned Son of Godzilla and Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster (1966). The abundant stock footage, combined with the shamelessly kiddo concept, is why Godzilla’s Revenge seems to be, across the board, regarded as the worst of the original Godzilla pictures – a dumb-ass clip show for kids.

But I smell repression. These same fans get a gleam, a glimmer, even a smile recalling how badass the picture seemed when they watched it as kids: a sort of “Godzilla’s Greatest Hits.” No matter how strange – or familiar – these glimpses of smog-filled late-Sixties Japanese childhood might have seemed to North American kids watching this shit on tape when it resurfaced in the Nineties, they only cost a few minutes’ patience between clip after clip of Godzilla whooping monster ass. And although those fights are barely altered from the movies from whence they came, they now have energetic, groovy, ass-kicking funk music cranking under them from Kunio Miyauchi, his sole composer credit on the series.

In fact, haughty criticism be damned, Godzilla’s Revenge is a funky piece of celluloid – even funkier than its Japanese version, in which the title roughly translates to All Monsters Attack (1969). For example, beyond selecting a badass title – which, unfortunately, has nothing to do with the film – the American shysters who repackaged All Monsters Attack for the Fast Food Nation cut the title montage – yet another clip show – under a completely eerie and bizarre piece of noir jazz. Supposedly, this is “March of the Monsters,” which the credits say is available from Crown Records. That appears to be wishful thinking on the distributors’ part: I’ve hunted for that sumbitch for twenty-plus years now and found no physical release at all, tracking the tune itself, in a slightly less haunting mix, to an early-Sixties piece of library music by Ervin Jereb, “Crime Fiction,” available from the Universal Music library. Nevertheless, the opening credits of Godzilla’s Revenge, in their goofy, surreal ghoulishness, are among the most memorable three minutes of the entire series.

Then there’s the funkiness of the picture itself, a funk scrubbed, to some extent, in digital releases. Analog issues of the movie have the charming murk of the original film print, which looks, in its later digital incarnation, white-balanced and shaved. But beyond the texture of the print, the very concept of the movie, its execution, is as funky as the finest entries of the series. Not quite as funky as Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster (1971), I’ll give you that, but comparably funky to Son of Godzilla or Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster in concept and possibly funkier in execution. Narratively, it may be the most down-to-Earth Godzilla picture Ishiro Honda directed, devoid of the grandeur of his other pictures, shrunk down to kid height.

It’s almost like Honda doing Jun Fukuda, who directed those aforementioned funky entries Son and Sea Monster, as well as the later classic Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). Whereas Honda’s entries in the series, which constitute the majority of the original Godzilla movies, had an ambitious apocalyptic grandeur, Fukuda’s had the high-flying, far-out comic book approach of the James Bond movies. Honda’s heroes were reporters and professors; Fukuda’s, pirates and islanders. Where Honda’s Godzilla fought giant months and three-headed space dragons, Fukuda’s fought giant lobsters, birds, and spiders. Honda had Akira Ifukube, who wrote big, operatic scores; Fukuda had Masaru Sato, who wrote surf music.

Criticism aside, it’s a fact many fans seem happy to overlook that anyone who grew up watching Godzilla pound rubber ass is something like little Ichiro the Loser here. Like him, many of us have imagined, a time or two hundred, what kind of perspective we might have seeing the Big G coming at us from a few miles away, how surreal that gigantic rubber suit would look to scale in the context of “reality,” how awesome it would be to have those four hundred feet of rubber come stomping on to the playground when some kid’s giving you shit.

I remember marveling that life in Japan went on like normal when everyone knew that, just off the coast, was an island full of tenuously contained giant monsters. Just shy of three decades later, having lived through a global pandemic, I now know that’s actually exactly the way it would go. “Yes, Ichiro, there is an island of giant monsters just off the coast – but we’ve still got the damn bills to pay!”

I last watched this on the 1992 Paramount/Gateway VHS tape, which uses “Master Sharp” technology to ensure the tape looks slick even when recorded in EP mode.

I'm convinced: We need a canon Godzilla rom-com to flesh out the Godzilla Jr. origin story. He's too goofy to go unexplained.